When Nicolas Vermont entered the greenhouse, he would make a gruesome discovery. It was the early 20th century in rural France, and Nicolas was visiting his uncle – a scientist and surgeon called Dr Frédéric Lerne – after 15 years apart. However, he had soon grown suspicious about his uncle’s odd behaviour, so for answers had decided to explore the grounds of his relative’s estate late at night.

Inside a greenhouse in the garden, Nicolas discovered that Dr Lerne had been conducting disturbing scientific experiments. At first, he saw plants grafted onto one another: a cactus growing a geranium flower, and an oak tree sprouting cherries and walnuts. His uneasy curiosity, though, soon turned to dread. ‘It was then that I touched the hairy plant. Having felt the two treated leaves, so like ears, I felt them warm and quivering,’ he recalled. Grafted onto the stem were the parts of an animal: the ears of a dead rabbit. ‘My hand, clenched with repugnance, shook off the memory of the contact as it would have shaken off some hideous spider.’ [Quotations from published English-language editions translated by Brian Stapleford; the rest are the author’s own.]

Dr Lerne was in fact an impostor. His assistant Otto Klotz had stolen the true uncle’s body through a brain swap, and would not hesitate to punish Nicolas for his ill-placed curiosity… by transplanting his consciousness into the body of a bull.

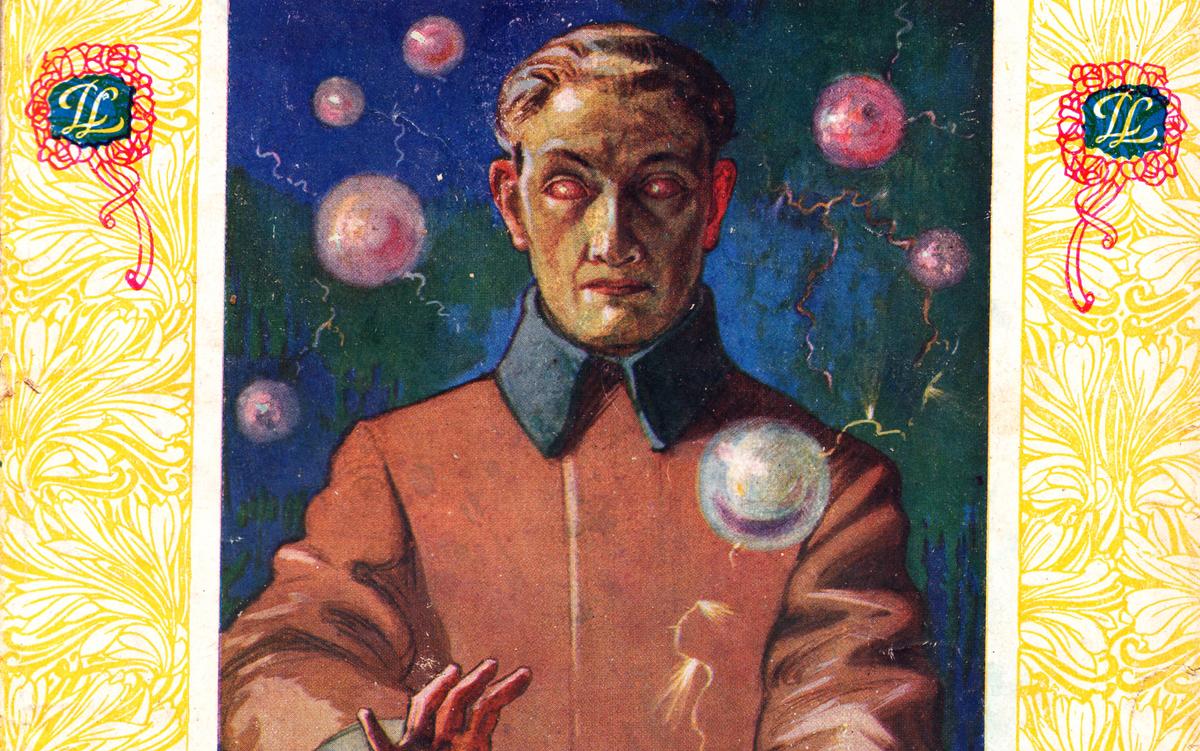

Le docteur Lerne, sous-dieu (1908), or ‘Dr Lerne, Demi-God’, was a celebrated novel by Maurice Renard, hailed by the poet Guillaume Apollinaire as a ‘subdivine novel of metamorphoses’. Published in English as New Bodies for Old, it heralded the dawn of a new French literary genre – one that ventured boldly into the uncertain and the unknown. Renard called it ‘merveilleux-scientifique’ (‘scientific-marvellous’) and its ambition was to help the reader speculate on what could be, and on what exists beyond the reach of our senses, rather than what will be. In other words, allowing a better understanding of what Renard poetically called ‘the imminent threats of the possible’. As he wrote in 1914, the goal was to ‘patrol the margins of certainty, not to acquire knowledge of the future, but to gain a greater understanding of the present’.

Rejecting the ‘scientific adventure’ storytelling of the celebrated French sci-fi writer Jules Verne – who had died only three years before the publication of Le docteur Lerne, sous-dieu – the merveilleux-scientifique genre was grounded in plausibility and the scientific method. According to Renard, only one physical, chemical or biological law may be altered when telling a story. This strict discipline, he argued, is what lent the genre its power to sharpen the reader’s mind, by offering a wholly original kind of thought experiment. For example, Renard modelled Dr Lerne on the very real surgeon and biologist Alexis Carrel, who had experimented with surgical grafts, transplants and animal tissues… to the point that he even grafted a dog’s severed head on another living animal (the attempt failed). Following in his footsteps, Renard imagines an exchange of brains – and personalities.

Leafing through the merveilleux-scientifique novels today allows for a dual rediscovery: firstly, it uncovers the previously unrecognised richness of Belle Époque scientific fiction, which did not perish with the works of Verne. The stories take in journeys to Mars, solar cataclysms, reading of auras, psychic control, weighing of souls, death rays, alien invasions, even strolls among the infinitesimally small. But exploring the genre also offers insights into the cultural history of the era, marked by a significant permeability between science and pseudo-science. Reading this work, we can learn a lot about the aspirations, fears and beliefs of early 20th-century Europe.

Perhaps more importantly, the lesser-known stories of merveilleux-scientifique allow us to question the official history of science fiction – a term that did not even exist in France at the time as it as it would be popularised in English by Hugo Gernsback only in the 1920s. Whereas today it is sci-fi writers like Jules Verne or H G Wells who are most remembered from this period, the merveilleux-scientifique novels were just as imaginative and visionary, but often far more provocative, daring and strange.

It was in October 1909, in the symbolist journal Le Spectateur, that Renard, who nicknamed himself the ‘scribe of miracles’, laid the foundations of his new genre, merveilleux-scientifique, with the publication of a manifesto-like text titled Du roman merveilleux-scientifique et de son action sur l’intelligence du progress, or ‘On the Scientific Marvellous and Its Influence on the Understanding of Progress’. Renard did not claim to have invented the merveilleux-scientifique genre, nor did he seek to assume its paternity; rather, he attempted to trace its lineage and establish its rules of composition in order to ensure its wider dissemination within the literary world. He wanted to mark a clear break from Verne (written down in his archives, his main purpose is to ‘demolish Jules Verne’), a highly symbolic act of patricide. Departing from works such as Around the World in Eighty Days (1872) or Michel Strogoff (1876), which recount journeys of peril and discovery, Renard distanced himself from the model of the scientific adventure novel.

Le fulgur (1909) by Paul de Sémant pays homage to Jules Verne with a search for ocean treasure and fighting sea creatures – but Maurice Renard rejected such ‘scientific exploration’ stories/cover by Marin Boldo, Paris, Ernest Flammarion

Renard also refused to engage in scientific popularisation or lengthy encyclopaedic descriptions, as Verne does in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), when he details the wondrous creatures visible through the porthole of the Nautilus submarine. Renard’s aim was not to teach scientific fundamentals or entertain young readers; rather, he set out to equip the critical minds of adult readers. As he stated:

The merveilleux-scientifique novel is a fiction based on a sophism; its aim is to lead the reader to a contemplation of the universe closer to the truth; its means lie in the application of scientific methods to the comprehensive study of the unknown and the uncertain.

‘Le Horla’ (1887) by Guy de Maupassant was not mentioned by Renard but it is a tale with a merveilleux-scientifique flavour: the protagonist is haunted by what he thinks is his double, a ghost, or maybe a creature from the stars/cover by William Julian-Damazy, Paris, P Ollendorf, 1908

By rejecting Verne, Renard claimed a very different lineage, drawing from both scientific and fantastical novelists. You might expect to find Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein (1818) or Guy de Maupassant’s short story ‘Le Horla’ (1887) on his list, but they were absent. Instead, one finds J-H Rosny aîné’s Les Xipéhuz (1887), which describes a struggle with a lifeform never encountered, as well as La force mystérieuse (1913), or The Mysterious Force, which imagines the harmful and eventually joyful consequences of a planet passing through Earth’s atmosphere. Renard also looked to Edgar Allan Poe, with his stories featuring magnetism, such as ‘The Facts in the Case of M Valdemar’ (1845) and ‘A Tale of the Ragged Mountains’ (1844), as well as Auguste de Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s L’Ève future (1886), or The Future Eve, a novel featuring an andréïde, an artificial creature designed to imitate a woman.

However, it is H G Wells, more than any other, who profoundly influenced Renard with works such as The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), which depicts unnatural hybridisations between humans and animals, and The Time Machine (1895), in which the hero travels through time and discovers the fate of humanity thousands of years in the future. Renard admired Wells’s audacity and his ability to use the novel as a laboratory for thought. This is why he dedicated his very first book, Le docteur Lerne, sous-dieu, to him.

Throughout his career, Renard would publish several theoretical texts aimed at establishing the rules for writing a merveilleux-scientifique story and defending its positive influence on readers. His novels followed an unchanging principle. There was no need to set the story in the distant future; it was always situated in the present world of the reader, where the novelist modified (most of the time) only a single natural law. Renard refused to imagine the future evolution of a science or invention already in place, as Verne does with the Nautilus submarine, which resembled the engineer Robert Fulton’s own Nautilus. Rather than imagining the future consequences of an invention, he preferred to imagine a deviation, a blind spot, not yet thought of in a science that was sometimes still confused in the minds of his contemporaries, such as radioactivity or the relativity of time. He also criticised how some writers prefer to write humorous tales set in the future, as Albert Robida does with Le vingtième siècle (1883), or ‘The Twentieth Century’. On the contrary, the merveilleux-scientifique narrative aims to explore ‘the unknown’ and ‘the uncertain’, to deeply question the human condition.

Le vingtième siècle: La vie électrique (1892) by Albert Robida imagines the all-electric, aerial Paris of the future/cover by Albert Robida, Paris, Librairie illustrée

One compelling example is in Guy de Téramond’s L’homme qui voit à travers les murailles (1913), or The Mystery of Lucien Delorme, which drew on the fascination and fears of radioactivity. The protagonist, Lucien Delorme, accidentally receives a grain of radium in his eye bandage, which grants him the ability to see through walls and other opaque objects, much like an X-ray machine:

That fragment of radium has been swept along, carried by the circulatory torrent … Your skull has become a radiographic device. You see with X-rays!

Similarly, in Louis Forest’s On vole des enfants à Paris (1908), or Someone Is Stealing Children in Paris, radioactive material is used to exponentially increase the intelligence of ordinary children and turn them into ‘supermen’:

To produce genius in the brain of one of my little fellows, I insert a particle – a grain – of this radium-flaxium at the very spot where lies the faculty, the intellectual function I wish to multiply a hundredfold.

L’homme qui voit à travers les murailles (1913) by Guy de Téramond/cover by Henri Armengol, Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1923

On vole des enfants à Paris (1908) by Louis Forest/cover by Jules Tallandier, Paris

Meanwhile, as early 20th-century surgeons experimented with transplantation, Renard wrote Les mains d’Orlac (1920): the story of an injured pianist who receives a hand transplant taken from a deceased criminal – which, supposedly, drives him to kill. It would inspire many films, from Robert Wiene’s The Hands of Orlac (1924) to Karl Freund’s Mad Love (1935).

There was no need to travel the world to experience thrilling adventures; a ‘motionless journey’ was enough

Similarly, in Octave Béliard’s Le décapité vivant (1931), or ‘The Living Decapitated Man’, a gorilla receives the head of a condemned man grafted onto its shoulder, which he tears away. With this tale, Béliard – himself a physician – was delving into a haunting theme of his time: that of post-Darwinism and the close kinship between primates and humans.

Le décapité vivant (1931) by Octave Béliard/cover by Alfred Dupuich, Paris, Le Livre de Paris, 1944

Renard liked to compare the merveilleux-scientifique novel – ‘an instrument of objectification’ – to an aquarium that can be viewed from all angles, or admiring a landscape through stained glass. For him, there was no need to travel the world to experience thrilling adventures; a ‘motionless journey’, to borrow the title of the collection Le voyage immobile (1909) by Renard, was enough. For this, one only needed to change their perspective on the surrounding world, sometimes in a literal sense. Take, for example, Gabriel Mirande, hero of Le lynx (1911) by André Couvreur and Michel Corday, who suddenly gains the ability to hear thoughts:

It was a chaotic tumult of ideas in his head, a cerebral activity a hundred times more intense than the most exhilarating drunkenness. He hugged his forehead with his hand, thought he was going mad …

Le lynx (1911) by André Couvreur and Michel Corday/illustrator unknown, Paris, Pierre Lafitte

The goal of the merveilleux-scientifique movement was simple: to help its readers better understand the contemporary world. Today, we take for granted that sci-fi can achieve this, but, a century ago, this was far less clear. While Renard depicted the threats that may arise from the unknown, including sciences not yet mastered, his stories did not focus on hypothetical futures, as he underlines in his archives: ‘I don’t want to anticipate, I’d rather pretend to spill out, if I had the slightest pretension.’ On the contrary, he engaged with his readers to offer them new tools to think about the world. As he explained in an unpublished letter sent to the critic Jacques Copeau, who had attacked his work:

I try to make my reader climb a still-virgin hill from which he will see the world in a new light, through distorting lenses that will help him better understand the proportions of normal vision, in a currently false light but which may one day enlighten us.

In reviewing Renard’s archives, it is evident that the writer was continually leafing through newspapers, looking for striking topics to inspire his narratives. He would scrawl on loose sheets significant scientific events, snippets of scientific popularisation, and even potential fictional applications of recent discoveries. Indeed, many of the merveilleux-scientifique novels were inspired by real experiments, discoveries and scientific hypotheses, which were widely disseminated in the media.

De Téramond, for instance, drew on research conducted on the luminous sensation caused by the approach of a radioactive component near the eyelid, as well as the widespread use of radiography. Forest, like several of his contemporaries, speculated on the energising or rejuvenating powers of radium. And Béliard was inspired by observations made at the foot of the guillotine, used to judge the reflex actions of a severed head, as well as the xenografting experiments conducted by Carrel and his student Serge Voronoff.

In his essays, Renard emphasised the necessity of writing a novel as one would pursue the scientific method. That is, even if the premises are false, the reasoning is still scientific. For instance, in Renard’s short story ‘Les vacances de monsieur Dupont’ (1905), or Mr Dupont’s Vacation, dinosaur eggs hatch due to intense heat as a normal egg would do. The merveilleux-scientifique novel thus presented itself as the ‘development of a hypothesis that is both logical and fertile’.

Le secret de ne jamais mourir (1913) by Alex Pasquier, which explored whether a man with no organs, only mechanical parts, could be immortal/illustrated by Cuyk, Paris/Bruxelles, Éditions Polmoss

The term ‘science fiction’ has sparked numerous debates among specialists, who sometimes substitute it with the term ‘speculative fiction’. When it first appeared, the term merveilleux-scientifique also raised questions due to its oxymoronic nature, juxtaposing two concepts that seem incompatible: magic and science. Renard himself would alter the label on more than one occasion, likely to gain greater acceptance from literary critics, referring to it as a ‘tale with a scientific structure’, ‘a hypothesis novel’ or ‘a parascientific novel’. Nevertheless, this designation allows one to grasp several prominent aspects of the genre immediately.

First, the term merveilleux-scientifique was not Renard’s invention. It had already been popularised by the physiologist Joseph-Pierre Durand de Gros in 1894 in an essay of the same name, which discussed the introduction of hypnosis at the Salpêtrière Hospital under the influence of the neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot and, more broadly, the gradual rationalisation of the supernatural. The term was used to capture the possibility that what was once considered marvellous might simply be science that has yet to be explained:

The matter is no longer open to dispute: the marvellous, the occult, the supernatural, now hold sway over classical science. Yet, if the marvellous dominates science, science in turn embraces it no less. They are thus imprisoned by one another.

In this respect, the novelists of the genre are perfectly aligned with their time. At the same time, the French astronomer Camille Flammarion speculated on what he called ‘unknown natural forces’ and dedicated several writings to metempsychosis (the reincarnation of the soul), as well as to psychometry (the ability to access the memory of objects by mere contact), while Pierre and Marie Curie attended séances with the medium Eusapia Palladino to observe her communicating with spirits.

Enchantment and wonder can still coexist with the most serious science

Metapsychics or parapsychology, a movement that encouraged scientists to investigate the fringes of science, deeply influenced the merveilleux-scientifique genre. In many of their novels, authors normalised marvels once considered supernatural using technology or scientific discovery. For example, in the short story ‘L’œil fantastique’ (1938), or ‘The Fantastic Eye’, Renard imagined an aspiring scientist who uses a photographic device to see creatures from another dimension, which turns him mad in return. Similarly, in La lumière bleue (1930), or ‘The Blue Light’, by Paul Féval fils and Henri Boo-Silhen, a photographic plate coated with a mysterious preparation allowed mind-reading.

La lumière bleue (1930) by Paul Féval fils and Henri Boo-Silhen/cover by Pem, Paris, Louis Querelle

Even more than the scientific investigation of phenomena once considered supernatural, the term merveilleux-scientifique also refers to the way in which enchantment and wonder can still coexist with the most serious science. The authors often revisited tropes from fairy tales, with the key difference being that these phenomena were made possible by the advanced knowledge of a scientist, rather than by the mysterious powers of a fairy godmother. Among these motifs are miniaturisation, duplication and invisibility, to name a few. For example, in Albert Bleunard’s Toujours plus petits (1893), or ‘Ever Smaller’, a group of scientists shrinks a little more each day, thanks to the mysterious action of an electrified bell. They set out to meet the insects and tiny creatures, each time marvelling at the strange appearance of their surroundings and the beings they encounter. In Le singe (1924), or ‘The Monkey’, by Albert-Jean with Renard, a scientist invents ‘radioplasty’, a way to clone only the flesh of human beings, since the immortal soul can’t be copied with the body:

Electrochemistry, Claude says calmly. Advanced galvanoplasty. Integral photography. It’s simple. And it’s beautiful. This liquid is not merely like the frosted glass of darkrooms; it is sensitised and produces direct positive prints.

Interestingly, the merveilleux-scientifique genre was not limited to fiction. Its characteristic spirit – namely, the coexistence of magic and science, the paranormal and rationality, in a constant balancing act – also permeated magazines and promotional materials. In 1932, the author René Thévenin, who was also known for his merveilleux-scientifique works such as Les chasseurs d’hommes (1929), or ‘The Manhunters’, wrote a series of scientific articles for the magazine Sciences et Voyages, followed immediately by the serialised story ‘Do We See the World as It Is?’, written in the style of a scientific experiment. In this story, the narrator imagines placing a miniature man in the grass, unaware that he has been shrunk. This leads to the character’s distress, as he believes he has been transported to an antediluvian world populated by dinosaurs, while he is facing a giant dragonfly or a praying mantis.

Les chasseurs d’hommes (1929) by René Thévenin/cover by Maurice Toussaint, Paris, La Renaissance du Livre, 1933

‘Si le monde n’était pas ce qu’il est…’ (1932) by René Thévenin/illustrator unknown, Sciences et Voyages

Similarly, in Voyage à travers l’organisme (1924), a pamphlet published by the Chatelain Laboratories to promote their quack miracle remedies, a story imagines a journey through the human body, during which the travellers witness the beneficial effects of the administered medications. When faced with the evident sign of alopecia, for instance, it is enough to take a pill of Urodonal, which is said to eliminate the accumulated uric acid.

Voyage à travers l’organisme (1924) leaflet/illustrator unknown, Paris, Éditions de l’Urodonal © Marc Madouraud

For some commentators, such as Serge Lehman, who has worked extensively to rediscover the merveilleux-scientifique genre in France and even published a comic book, La Brigade chimérique (2009-10), or ‘The Chimeric Brigade’, inspired by these authors and characters, this literature represents both a ‘golden age’ and an overlooked cultural phenomenon. ‘Maurice Renard should have been the great theorist of the genre, the man of synthesis,’ he wrote in his anthology Escales sur l’horizon: seize récits de science-fiction (1998), or ‘Stopovers on the Horizon: Sixteen Great Science-Fiction Tales’. ‘And he was, in fact – but after the war, meaning too late to exert any significant influence on his contemporaries.’

American science fiction benefited from well-established magazines, reader correspondence and a social network

In some cases, Renard and his fellow authors were decades ahead of their time. For instance, the people with electric vision in Renard’s L’homme truqué (1921), or The Doctored Man, and the man-like felines in Félifax (1929) by Paul Féval fils, illustrate that France had already, in the decade following the First World War, imagined its own superheroes.

L’homme truqué (1921) by Maurice Renard, in which the prisoner of a mad German scientist is subjected to terrible experiments that give him the ability to see electricity/cover by Louis Bailly, Paris, Pierre Lafitte, 1923

Félifax (1929) by Paul Féval fils, in which an unethical surgeon inseminates a woman with genetic material from a tiger/cover by Bruhier, Paris, Éditions Baudinière

How can we explain the gradual disappearance of the merveilleux-scientifique from collective memory? The explanations are numerous, yet never entirely satisfying. First, Renard, who was financially strained after a divorce and embittered by critics, gradually transformed his genre, blending it increasingly with detective stories or romance novels. Moreover, unlike American science fiction, which benefited from well-established magazines, reader correspondence and a solid social network, merveilleux-scientifique never had such clearly defined boundaries. Some authors dabbled in it by chance, only to return to other styles. This, however, does not mean that this literature was not omnipresent at the time. It was widely published in popular editions by publishers such as Pierre Lafitte, Ferenczi and Jules Tallandier, often with particularly colourful covers:

For the anglophone audience wishing to discover these texts, they have fortunately been partly translated by the science-fiction writer and Wells expert Brian Stableford. Through such tireless work, we can continue to witness how this period’s fiction had already proposed itself as a magnifying tool for understanding its present.

It is not uncommon for people to ask me what led me to study merveilleux-scientifique, a journey I began 10 years ago. Never having been much of a science-fiction enthusiast, it was chance, or perhaps serendipity, that led me there. During my doctorate, I was fortunate enough to stumble upon the website created by Jean-Luc Boutel, Sur l’Autre Face du Monde (‘The Other Side of the World’), a goldmine assembled by this great connoisseur of science fiction. It was love at first sight – for those delightfully dated images, and for those texts I had never heard of before.

Along the way, I have met many erudite minds who had been working for decades on early speculative fiction, yet without receiving the recognition they deserve. The history of merveilleux-scientifique and its long neglect ultimately tells another story: that of the enduring resistance of the French academic world to acknowledge the worth of speculative literature, and the extraordinary groundwork laid by passionate readers, amateurs and collectors. In their company, I discovered a wholly different way of doing research – wandering through old book markets, indulging in compulsive reading, trading books, and engaging in collective exploration. If today I cherish merveilleux-scientifique, it is, of course, because this genre possesses an undeniable literary richness – one that teaches us much about its time and about the broader history of science fiction. But above all, it is because through it, I have had the privilege of taking part in a vital collective endeavour: to protect, gather and disseminate this memory, to ensure it is no longer forgotten. Every reader who opens a merveilleux-scientifique novel today adds their own stone to the edifice.