India is betting on Chinese technology to keep its electric-vehicle transition on track.

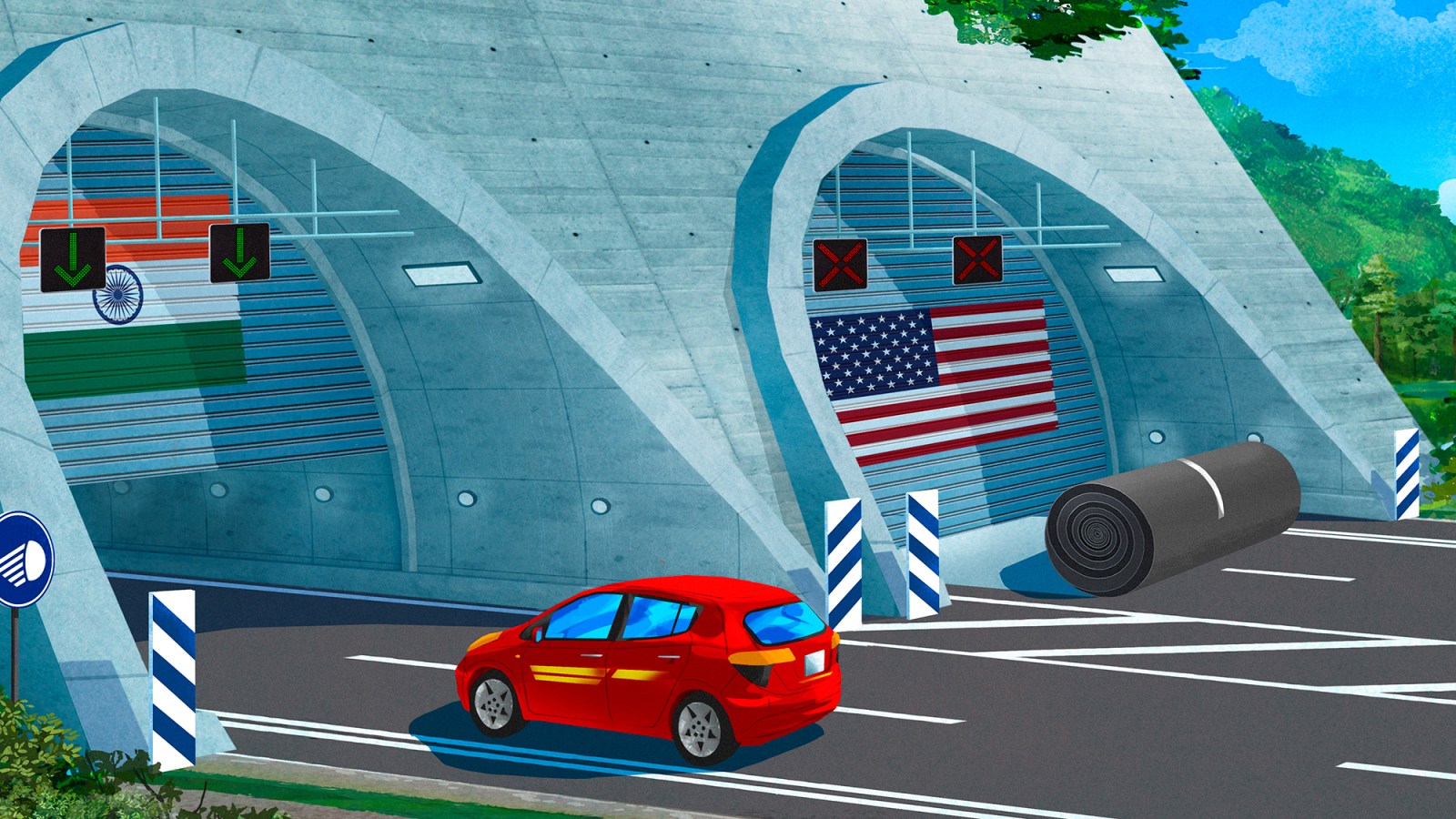

At a time when the U.S. is erecting trade barriers to keep Chinese EV giants at bay, India has taken a different course.

“Without Chinese tech, India would face supply shortages, delayed rollouts, and reduced product diversity,” Pragathi Darapaneni, senior battery materials scientist and former researcher at Argonne National Laboratory, told Rest of World.

India’s own EV makers are struggling as the government revamps its subsidies to drive local innovation and investment. The country is relying on Chinese tech to bridge the gap until the domestic players are more robust.

The shift is happening with no fanfare. Since deadly border clashes with China in 2020, India banned apps like TikTok and Shein, and blocked Chinese automakers like BYDBYDBYD Auto is a Chinese carmaker that became the world’s leading EV manufacturer in 2023, competing with Tesla for market share and global attention.READ MORE from setting up a local factory, citing national security concerns. Yet, Chinese technology remains central to India’s EV ambitions. In late March, India cut tariffs on over 35 EV components, most of which still come from China, making the tech exchange between the two countries even easier.

Big Indian EV makers, such as “Tata Motors, Mahindra & Mahindra, Ola Electric, etc., still rely on Chinese suppliers for [lithium-ion] cells and power electronics components, even if final assembly is done in India locally,” Shubham Munde, a senior analyst covering tech at research and intelligence firm Market Research Future, told Rest of World.

“The aim is to build a resilient domestic ecosystem, not to isolate it, unlike the more aggressive decoupling seen in the U.S. with China,” Munde said.

Indian firms opt for joint ventures with global players — mostly Chinese — to gain both capital and shortcuts for R&D timelines. These partnerships help them “leapfrog development stages by accessing tested EV platforms, battery modules, and manufacturing playbooks,” Leon Huang, CEO of RapidDirect, a global precision manufacturing company that supports EV supply chains, told Rest of World.

Chinese firms “also help local partners [in India] build supply chain reliability and achieve faster localization by starting with preexisting part libraries and manufacturing standards,” Huang said.

Such collaborations have shaken up the Indian market. Tata Motors, the country’s leading EV maker, has seen its lead shrink as MG Motor — a joint venture between Indian conglomerate JSW and China’s state-owned automaker SAIC — doubled its market share within a year. The MG Windsor, now India’s best-selling electric car, came out of that collaboration.

For the past few years, India has offered generous incentives to carmakers to make EVs affordable, especially scooters and three-wheeled vehicles that dominate its roads. Yet, only 7.6% of new vehicles sold in India were electric in 2024, a slow pace for a country aiming for 30% electrification by 2030.

The government’s new eligibility rules for subsidies require companies to fully assemble EVs within India while allowing the import of components that are not yet produced domestically. Purchase incentives for consumers are also shrinking.

The overhaul has laid bare the fragility of India’s EV sector, with consumer funding down 37% from $934 million in 2022 to $586 million in 2024, and EV sales starting to slump. Tata Motors’ EV fleet orders fell from 26,000 in 2023 to just 2,000 vehicles in 2024.

Hero Electric, India’s first e-scooter manufacturer, is facing bankruptcy proceedings and being probed for not meeting the government’s subsidy requirements; BluSmart, an EV-focused ride-hailing Indian startup, has shut down; and the country’s largest EV maker Ola Electric is losing ground.

Bernstein Research estimates that four legacy automakers control 80% of India’s electric mobility market, while most of the country’s 150 EV startups are “grappling with losses.”

India’s EV market is projected to grow from 480,000 units in 2025 to over 3 million units by 2035, according to a forecast by London-based data analytics firm GlobalData.

The expansion requires a robust EV supply chain, Vivek Kumar, an automotive project manager at GlobalData, told Rest of World. “India still faces significant challenges. A shortage of technical expertise and an underdeveloped charging infrastructure continue to hinder progress,” Kumar said.

EV-related imports are among the key contributors to India’s growing trade deficit with China, data from India’s Commerce Ministry shows. Experts warn overdependence on China could undermine India’s goal of developing its own EV technology.

“India should be careful that such partnerships do not lead to Chinese players dominating the market, as this could reduce incentives for developing domestic companies and technologies. There needs to be a balance,” Jason Altshuler, owner of My Electric Home, a Colorado-based provider of innovative electrical solutions including EV chargers, told Rest of World.

Opening market access to China poses both a strategic and security risk for India. Chinese firms face intense scrutiny in India due to geopolitical rivalry. But New Delhi has avoided the U.S.-style curbs on Chinese technology.

Tu Le, founder and managing director of Detroit-based mobility intelligence and advisory firm Sino Auto Insights, sees U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariff war on Chinese EV components — particularly batteries — as an obstacle to America’s EV growth. Le told Rest of World the U.S. has lost the EV momentum built over the years, and Trump’s EV policy “guarantees the U.S. won’t go any further on continued EV sales.”

India is choosing soft protectionism, aiming to “integrate with — not isolate from — Chinese supply chains until substitutes mature,” Munde said.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply