When I started at the Department of Education in the 1990s, student loans were a popular middle-class benefit. College affordability was rarely front-page news. Our dingy offices, a converted World War II warehouse, were a daily reminder of how our work seemed overlooked, too. But in those hallways—literally, my desk was in a hallway—we celebrated lower interest rates, fewer loan defaults, and record college enrollments.

When I returned to the Education Department a decade later, reports of deceptive recruiting tactics at for-profit colleges raised new questions about the value of college loans. My bosses wanted to know whether these abuses were widespread. Were they a few bad apples or a rotten orchard?

College degrees still led to huge earnings gains, on average, for students who were awarded them. The Department of Labor economists pegged the value of bachelor’s degrees at $1 million over a career. But there was very little data on the actual payoff from any particular college or program.

Instead, we looked at a simple proxy to measure the program’s value: whether loan balances were growing or shrinking. If interest accrued faster than borrowers could pay it down, that was a problem with student loan debt. We thought that might be the case for about a third of borrowers who recently left school. But the real number gave me a knot in my stomach. It was double our estimate: more than two-thirds of students saw their loans getting bigger, not smaller, over time. And while some caught up after years in repayment, one in three borrowers were still underwater, even on the oldest loans in the analysis.

These data led Barack Obama’s administration to set minimum standards for for-profit colleges and career programs, protecting hundreds of thousands of students from unaffordable debts. But there remained a larger question: How many students had education loans they would never pay down—and what would become of them?

By Jillian Berman, The University of Chicago Press 320 pp.

In her new book, Sunk Cost, Jillian Berman sets out to explain how student loans went from a widely supported student benefit to a generational grievance. Covering the student loan industry for over a decade at the financial news service, MarketWatch, she explains how the student loan programs evolved, revealing how key policy decisions ultimately affected the lives of individual students.

In Berman’s telling, policy debates have a familiar echo from decade to decade. Political leaders call for the opening of the doors of college to everyone, regardless of income, but few were willing to invest the money necessary to pay college costs. Student loans were how they reconciled lofty ideals with paltry budgets.

“Lawmakers were interested in expanding access to college,” Berman writes, but “they wanted to keep costs to the government low. Crucially, policymakers were confident that students would benefit financially from their education, which justified the idea that students should be investing in it themselves.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson created the federal student loan program in 1965, saying, “This nation could never rest while the door to knowledge remained closed to any American.” But his student loan program was “trying to hold the budget down,” according to the New York Times.

Johnson, Richard Nixon (who signed Pell Grants into law in 1972), and Jimmy Carter argued that making college affordable was in the country’s and individual students’ best interests. That view changed under Ronald Reagan. As governor, Reagan imposed the first tuition charges at the University of California. As president, he starved Pell Grants of funding. As his Secretary of Education Bill Bennett said, “Students are the principal beneficiaries of their investment in higher education” and therefore should “shoulder most of the costs.”

Other themes echo through the decades: Ostensibly a benefit for students, loan programs were shaped by commercial interests, intentionally providing ample profits to financial institutions. Quality standards were watered down to benefit for-profit colleges. Student aid programs also tolerated or even exacerbated racial disparities, even before the advent of LBJ’s student loan program. The G.I. Bill funded a segregated system of higher education. Tuition hikes in California and other states coincided with the growing enrollment of students of color. Black students were—and still are—more likely to go into debt, borrow more, and struggle to repay their loans.

To assess these policies, Berman relies on the voices of borrowers. Her reporting is filled with arresting accounts: single mothers piecing together child care around full-time jobs and full-time course loads, students lured by false promises and left with unpayable debts, some never finishing, others graduating only to find their degrees worthless, and some carrying student debt into retirement.

Crippling student debt is often painted as the consequence of irresponsible decisions. But, as Berman points out, it usually isn’t a choice at all. Many of these borrowers believed they were enrolled in the cheapest college they could find or that it represented their only option for post-secondary education.

Looking for a chance to be her own boss, Patricia Gary enrolled in a Bronx beauty school. The instruction was poor, and she dropped out owing $6,000. Over the next 30 years, as an educator and social worker, she repaid $23,000—sometimes through garnished wages and tax refunds—but could not repay her entire loan. Her balance was finally forgiven at age 75.

Sandra Hinz returned to school in her fifties to become a medical assistant. But when her adult son became disabled in a motorcycle accident, she was forced to become a full-time caregiver. She struggled to get help with her $28,000 loan despite income-driven repayment plans designed to help people like her.

As a young mother, Kendra Brooks attended community college for seven years, followed up with a four-year degree and an MBA at age 50. She borrowed $50,000 over the years to pursue economic security for her family. Now, a Philadelphia council member, Brooks, says that her personal experience—and that of her constituents—is that college never quite pays off.

I have met many people with similar stories. But student loans are a double-edged sword. Many borrowers do graduate and go on to successful careers. Economists say that, at least at current tuition levels, loans increase graduation rates and pay off in the long run. Berman never grapples with the question of whether, in some circumstances, loans might be a reasonable way to pay tuition bills.

But the numbers also say that it is not rare for borrowers to be worse off than if they had never gone to college. Before the student loan pause during the pandemic, a million students defaulted on their loans yearly. One in three borrowers never graduate. Typical Black borrowers owe nearly as much as they borrowed, even 10 years later, having made no dent in the principal. The experiences Berman describes may not be universal, but they are far from isolated anecdotes. The stories and data suggest something is seriously wrong with the student loan program.

As I was peering at my charts around 2010, the student loan debt problem was getting worse. The Great Recession triggered state budget cuts, increasing tuition and student borrowing. For-profit online universities boomed, leaving millions with unaffordable debts. Graduates struggled to find footing in a weak job market, making their loan payments even more burdensome.

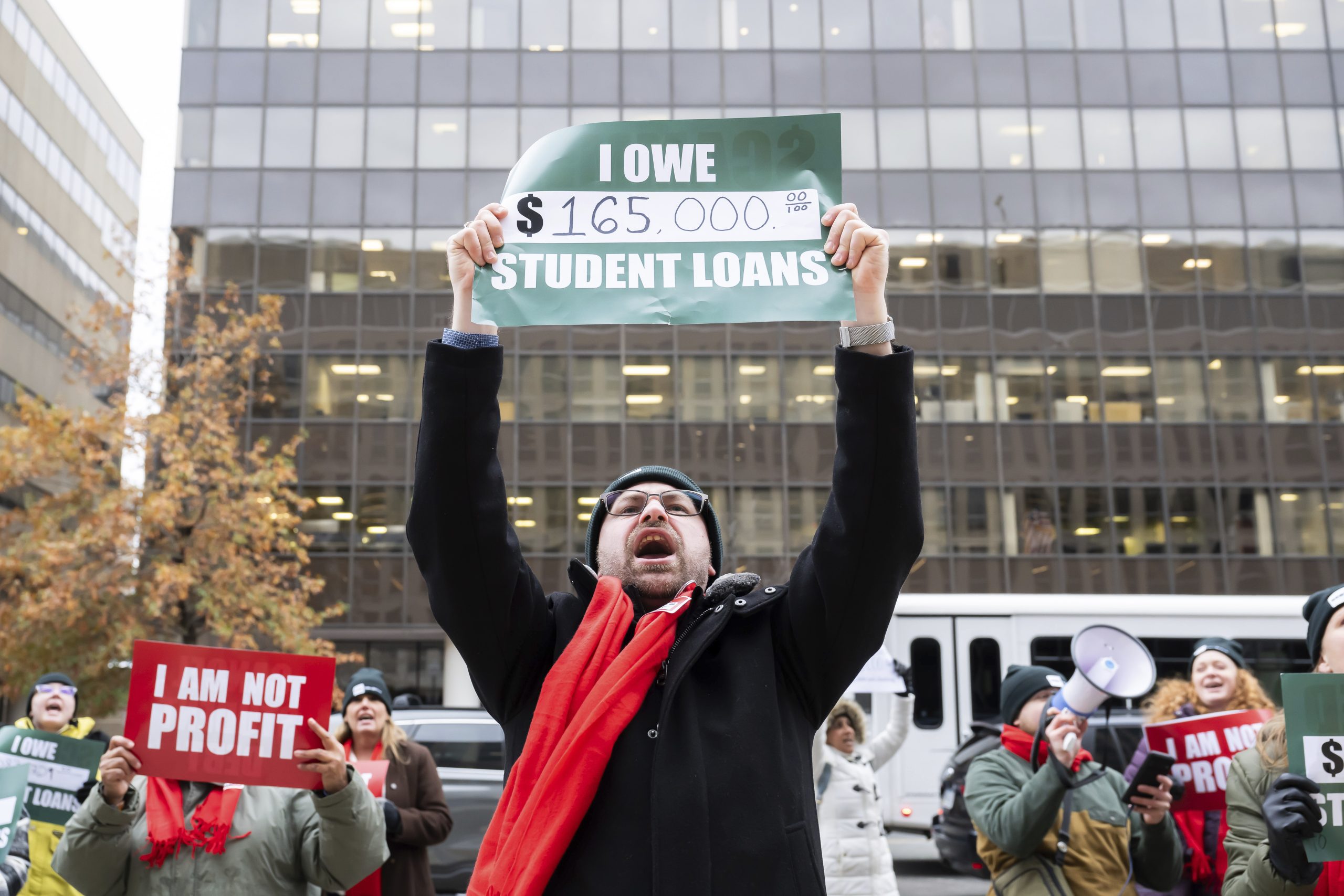

Around the same time, a political movement was brewing in Zuccotti Park in lower Manhattan. The Occupy Wall Street activists called for free college, student loan debt cancellation, and broader economic reforms. From that ferment emerged the Debt Collective, a determined and idealistic group of borrower activists.

Berman describes how the Debt Collective spent years raising grassroots funds to buy and forgive defaulted loans. They organized borrowers cheated by their colleges to press for their legal rights. They recruited allies to push for change through the political process.

In 2020, one of their allies, Senator Elizabeth Warren, then running for president, made debt cancellation mainstream with a campaign pledge to forgive up to $50,000 in debt for each borrower. It resonated. Soon, other presidential candidates joined her, as did teachers’ unions, civil rights groups, and a new cadre of borrower groups like the Student Borrower Protection Center.

When President Joe Biden won the White House in 2020, the focus turned to executive action rather than legislation. In 2022, Biden canceled up to $20,000 in debt per borrower. But only months later, the Supreme Court struck down the Biden plan, finding it to be an executive overreach.

President Biden advanced a second set of student loan reforms that received less attention but had a similar price tag, were intended to be permanent, and provided complete forgiveness to struggling borrowers. The Washington Monthly called the Saving for a Valuable Education (SAVE) repayment plan a “revolutionary” solution for borrowers with low incomes and large debts. The administration also broke down the bureaucratic obstacles within existing loan forgiveness programs—for public servants and borrowers with disabilities, among others—from discharging the entire loans of 5 million borrowers, including several people Berman profiles. But the income-driven SAVE plan is now tied up in courts, and the Donald Trump administration laid off entire teams that help borrowers receive benefits.

So, where do student-loan borrowers go from here?

Berman says we need a “philosophical shift to change our higher education system to one in which individuals take on less of a risk and taxpayers take on more.” She calls for fixes to the student loan program, “truly free” options at public colleges, and addressing broader economic issues that have made college—and therefore student loans—feel indispensable to young people.

Right now, Congress is going the other direction. The Republican budget bill would cut Pell Grants and make loans more expensive for many borrowers, redirecting some $300 billion to help pay for tax cuts that accrue primarily to high earners and corporations. Republicans also plan to cut off loans for programs whose former students have low earnings. In principle, this is right—we should stop making loans, as we know borrowers will not be able to repay them—and a spirit similar to Biden’s college accountability rules.

But without replacing more loans with more scholarships, the Republican plan will only encourage higher-cost private student loans and push college further out of reach for low-income students and students of color. It would also whittle down the goals of college to students’ future earnings at the expense of upward mobility, public service, religion, the arts, and many other social goals. A better approach would replace loans with a combination of free college, scholarships, and student loan benefits, especially for students who did not receive the ordinary economic benefits of a college degree.

We can also make college a more reliable investment. Over the last decade, we have boosted the college graduation rate by 8 percentage points, but it is still only 61 percent. Leading colleges have found ways to help many students graduate and then connect their degrees to promising careers, using data and fostering advising and counseling. But we have not yet invested in making those steps the norm, particularly at the community colleges and regional public universities that serve most students.

Readers wondering how debt relief became a top-tier political issue should confront the stories in Sunk Cost. It tells the same story as that chart I saw over a decade ago: The system is not working for a sizeable share of borrowers. A new approach to college finance, with substantial new investments, is needed to finally take advantage of higher education’s potential to build stronger lives and a stronger society.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply